peter

nesteruk (home page: contents and index)

|

|

|

|

|

|

GaoBo (I) (

Wondering in the Land of the Lost (The Art of Critical

Landscape).

‘Abode where lost bodies roam each searching for its lost one. ‘

(Samuel Beckett, ‘The Lost Ones’)

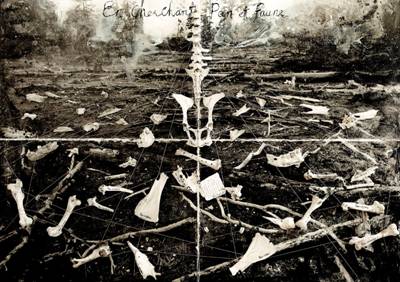

Bones, like a

curtain, overlay a landscape photographed, documented, then painted, a cleared

ravaged land - overlaid by bones, attached by a web of wires and numbered. The

art work, ‘自然安 魂曲 – 寻找潘神’ (2011) ,which includes the

handwritten words, ‘En Cherchant Pan et Faune’ (In search of Pan and Fauns),

offers Nature as despoiled… with the concomitant inference that the Culture

that does this is to be put in question. Because a culture that does this is

itself despoiled.

Sometimes it is necessary to return to basics in order to

analyse the impact of emotionally-moving and thought-provoking art works: genre

is most basic element in the recognition and evaluation of any given cultural

artifact; in all the arts we look to the genre for guidance and a prepared

lexical field. If the physical and institutional framing of an art work is the source

of its first definition or recognition as such, then genre is the first key to

meaning - its semantic frame. Landscape is one such a repository of meaning,

provocation of significance. (When the Landscape in question includes elements

that may be considered as Found Objects, so offering a sense of installation,

then we also access the range of responses we associate with the Still Life,

genre of the transfiguration of the everyday, sometime bearer of the gift of

luminescent sacrality).

The history or tradition of the Landscape charts a course from

religious and mythical content to a record of possession (a witness to wealth)

to (as an echo of the first stage) a representation of the ideal (Landscape as

desired place of beauty, desired heavenly dwelling place, vision of heaven on

earth). The second phase of the Landscape reappears now as returning us to our

‘possession’ as a record of our

possession (what we have done with our ‘birthright’) with the associated

religious and mythic force now found to be criticizing this ‘possession’ –

criticizing our record of

stewardship. The ideal Landscape returns to us only in its negative guise, as a

belated awareness of the lack of manifestation of this ideal.

Furthermore in an updating of two key terms inherited from art

history, ‘the Beautiful’ and ‘the Sublime’ may now be read as including, not

only an appraisal of our stewardship or relation with Nature, but also

increasingly of the ‘landscape’ of culture, of the mindset and actions that

produced this landscape, so of our history. The critical Landscape becomes the

critique of culture, of human history. Yet, in turn, recent history provides us

with the background to landscape; the new context on which we situate the

modern day genre of landscape - the ‘landscape of landscape’ so to speak. (This

background is perhaps most in-formed by the post-war landscapes of Anselm

Kiefer). Such landscapes are not beautiful. So in a revived use of ‘the

Sublime’ we are offered the predominance of the negative or the ironic. Nature

(actually presented as a product of agri-culture) is presented as a critique of

culture (so of the culture that made it) as dystopian; our cultural landscape

is seen as not living-up to our ideals or, more realistically, to our

potentials. Nature is no longer the scene of authenticity (unless that of an

‘authentic’ wound) much less the backdrop to moral regeneration and the renewal

of potential. An Anti-Pastoral. Art work in which only a trace of a reminder

(of the original Pastoral vision) remains… We are left with a deictic

indicator, a ghostly indication of pastoral remains, what remains of the

utopian, of ideal remains; there remains only enough to motivate a ghostly

contrast, to criticise the present.

If the Modern(ist) landscape was the continuation of the

Romantic landscape (‘by other means’) then it continued the critique of the

urban, of industry, technology and scientific or utilitarian reason (as well as

the tradition of a standpoint which was anti-mass culture, anti-mass society and anti-mass democracy, which later

aspect was taken over by the neo-feudal responses to the crises of

industrialization and nationalism). In the later half of the twentieth century,

the Modernist landscape was subsumed by the Post-modern; continuing the force

of critique, but now shorn of its anti-democratic elements (rather celebrating

aspects of mass culture). Yet still continued is the element, taken over from

modernism, of experiment and difficulty (albeit on differing grounds). Yet

critique and experiment in Post-modern form, as evinced in the ‘combine’ and

installation element (formal) together with the lack of backward looking

indexes as the cure for the Fall (content), all suggest that the simple

solutions touted in the past have all been eschewed. In terms of moral

propositions we find we inhabit a negative landscape. A landscape of problems.

A landscape of the lost…

As once we

searched for the Grail that would provide the answer to the question of meaning

and value amid the depths of the forest, searching for the glimmer of light

that would lead the way to a clearing; so now amid the ravaged remains of the

cleared forest we discover that the glimmer was something that we always

carried within ourselves. A Manichaeism stripped even of its distant and absent

God. Leaving us alone and lost in the deforested spaces of the soul.

Found Objects, when they appear against the background of a

Landscape, may suggest yet another genre, another field of meaning. In the work

in question these (the bones carefully arranged upon the face of the canvass)

amount to a 3-D reference to the realm of the ‘Still Life’, accessing its

lyrical power and appeal to beauty as residing in the object itself and in its

relations within a formal arrangement. A tradition dating from the earliest

Christian art as representing symbolic (religiously-charged) objects gathered

together, initially appearing in church walls (7th-8thc, echoes of

the frescoed decorations of Classical society) to its heyday in the 16th

and 17th centuries whose significance included possession and

beauty, objects and their interrelation as form, the transformation of the

everyday (but also included carcasses etc, echoing the meanings accreting to

the momento mori, the death’s head Vanitas of the Baroque, itself a feature

of the Still Life of the period). The current meanings of Found Objects and the

Still Life are often more ironic, more iconoclastic, than beautiful - so more

useful for conceptual ends. Now, as incorporated into a Globalised

Post-conceptualism, the hybrid heir to sculpture as ‘combine’ or

‘installation’, offering a celebration and critique, a presenting and

questioning of modern society, whose jumble it re-presents, as a cut-up, or

found object poem, at once a lyrical elegy for what might have been, and a carnivalesque

affirmation of (post)modern identity.

So Nature is represented by bones, by dead things, matter that

still remains, signs of previous life… (prosopoeaeic evocation of an absent or

lost life) and their arrangement into a Still Life, (nature mort in French). But here the Still Life is still indeed, is

dead, mere index of a former state; in the subjunctive mood only is future

‘life’ again possible. Art is memory work. Indeed in another work, ‘献曼达’(2009)

we see a collection of stones, each with a face (echoing the memorialising

works of Boltanski); we witness the superimposition of an image upon a stone

for the remembrance of a life; ’head stones’ in the graveyard of memory. Found

Objects and the Still Life in this sense are religious ‘fetishes’ - with the

word ‘fetish’ used in the proper sense of the word, as something, precious,

profound, sacred, so to be protected, remembered (and not as used in its

Enlightenment-rationalist, or intellectual neo-colonialist, form as a put-down,

or negative comparative, for the religious -non-rational- beliefs and practices

of other social forms; whilst remaining blind to the beliefs implicit in modern

forms of identity, or denouncing all non-rational elements of human culture).

If the celebratory end or appropriation of cultural objects offers a cultural

landscape as collage as collection, as fragmented modern experience as

positive, as pleasure, as jouissance, then

the more thoughtful end of this appropriation, through its lyricism, points to

something absent or lost, conjures up other modalities of reflection and

feeling, pointing to a ritual of ‘remembering’; remembering what is important…

asserting an identity focused upon reflection and value (also reflexivity and

value, with the paradoxes of ironic self-consciousness and the necessary

performative assertion of value(s)). Performing a quest (ritually, as art only

can): searching for (and in so doing, creating) meaning (as humans only can).

Still Lives:

Found Objects. Lost; what is lost? Lost object(s). Replaced by found

object(s)…so ‘found objects’ represent what is lost, lost objects, symbols of

what is lost… Or what is to replace what is lost?

|

|

|

|

|

|

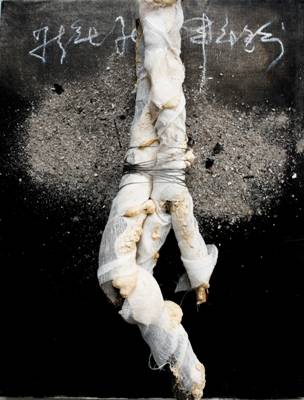

In, ‘迷失者的岸’ (2010) we experience Beckett as ‘Beckett’; the

Proper Name as a cultural referent which includes the impact of his works, as a

lost self as existential uniqueness and isolation, existential ‘thrownness’, as

well as dilemmas of moral choice in a post-foundational world: asking the

question: whence value, whence morality? Unfounded but necessary. Inferred in

art. (Since Romanticism offering art as a source, or interpretation, of value

in the world – at once symptom and diagnosis; an alternative source of the

sacred). A ‘thrownness’ applicable collectively to ourselves as a species (as

in Beckett’s short prose work, ‘The Lost Ones’). We have found ourselves as

lost; are ready therefore to found ourselves anew, to reinvent values - to

discover (to assert) values where we no longer can support beliefs…

The presence of water in the Beckett installation also taps into

a history of symbolic significance. Water (apart from its conjunction with

‘Earth’ as an element of landscape), more precisely the view across water,

connotes ‘the other-side’, and ‘crossing’… as well as the open space of light

that seems to hover above it. The sense of ‘crossing’ carries a ritual sense,

suggesting the image as capable of holding ritual force, and so of the

consideration of landscape as ritual, as a means of purification (again via

Nature, in tradition of Pastoral from Theocritus through the Romantics

–climaxing, in Wordsworth’s ‘epic’ ‘The Prelude’, with Nature as final cure for

all ills, intellectual and moral, individual and social- to William Empson and

D.H. Lawrence and taking a last gasp in the counter-cultural authenticism of

the 1960s). Today’s Post-modern pastoral is, however, ironic, a negative

pointer back to a lost former ideal (the naiveties of the Culture and Nature,

town and country, opposition have been surpassed, and are employed with an

awareness of their limitations). (Chinese equivalents of this, pro-Nature,

moralist, authenticist, tradition, would begin with Daoism (Yang Chu, Laozi,

Zhuangzi) and extend through Wang Anshi and Dai Zhen to the 20thc philosophy of

Jin Yuelin). Such scenes again access ‘the beautiful’ in art. Deploying

sensuous pleasure as calming, reflective and orderly, whilst suggesting

something else, something absent, wistful, even melancholic (so not a ‘pure’ or

ideal classical form of beauty). Something we can find in many water scenes;

poignant, with loss…inviting, or suggesting, redemption. Cross the water.

Landscape in

one of its related forms, the Pastoral, here as always connoting Nature,

appears in a ‘beautiful’ form as loss. And in ‘sublime’ form as an

anti-pastoral; the pastoral lives on as Complaint, itself damaged by the very

culture it would denounce, present as a wounded scene calling forth an absent

cure…

Or a fertility rite… a rite of Spring. Rite of rebirth.

|

|

|

|

Genre as a marking-of, a re-framing, an intensification of

meaning. (Art as ritual. The ritual face of art.)

Installation: a machine for making meaning (for making

feelings). As with the frame of the picture (augmented by the gift of time of

the viewer), so to the framed space of the installation offers the significance

only available to ritual. Most basic function of ritual: our recognition of

ourselves.

To be lost in

the world; to be at a loss before the world. To be at a loss before a world… to

be lost to another world…

|

Copyright Peter Nesteruk, 2013